Sharing is caring!

To see the other posts in this series click HERE.

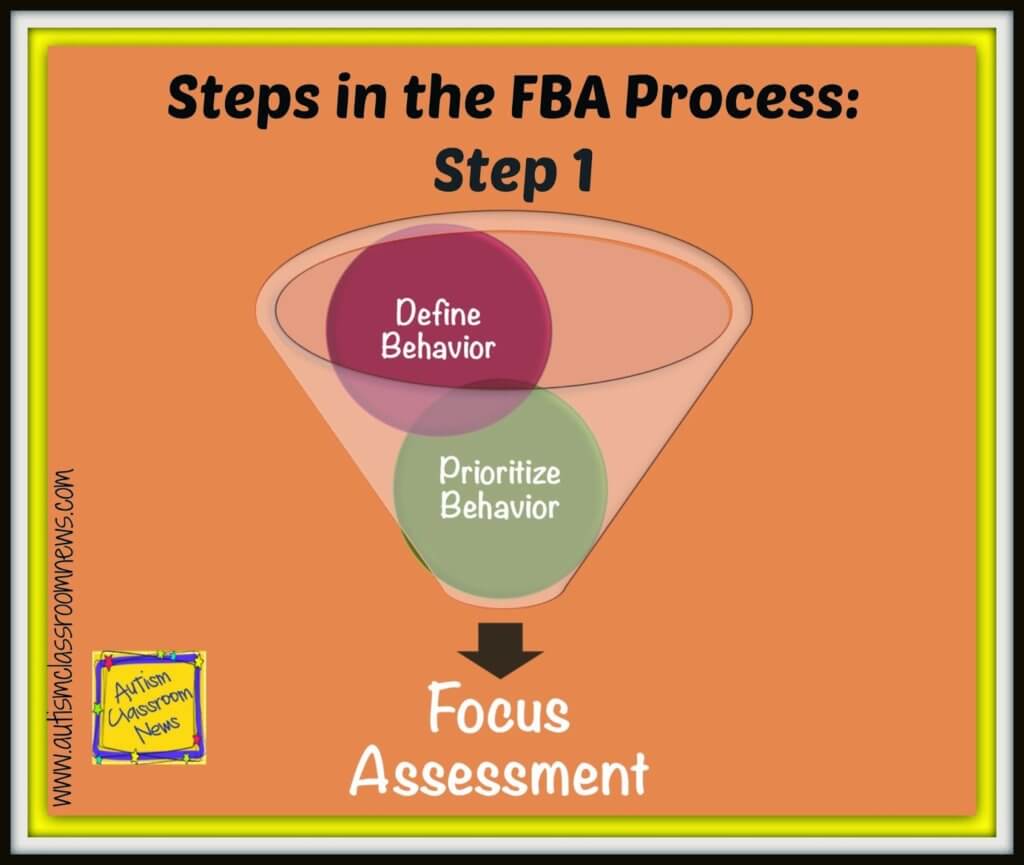

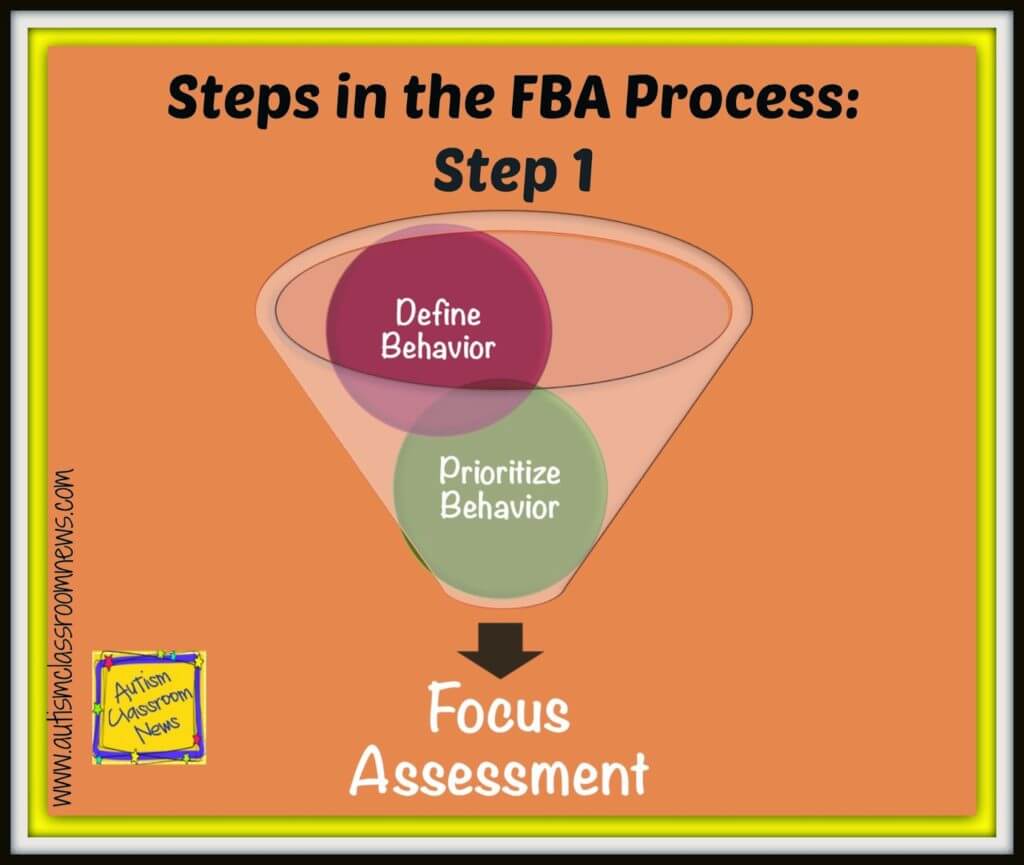

So, picking up where we left off from the overview of the 5 Step process of behavioral support, the first step is to focus the assessment through defining and prioritizing which behaviors need intervention and which ones we should intervene with first. This is one of only times where the form of the behavior is as important as the function. If we haven’t clearly defined what the behavior looks

like, we can’t start the assessment and observe the behavior.

In order to assess a behavior, we need to make sure that we all understand what we are looking for so we can observe it. For instance, when I say a Walter had a tantrum, what do you think he did? Did he fall on the ground? Did he scream? Did he cry? Did he throw things? Did he tear apart the room? Did he hit people? Did he whine and stamp his foot? The description of a tantrum varies significantly between people, as do come-apart (one of my favorite catch-all terms from my friends in the south) and meltdown. Even aggression is difficult to identify if we don’t define it clearly–hitting? kicking? and I even have some folks who would include yelling as verbal aggression. If we are all observing and recording different behaviors that aren’t well-defined, our data won’t match up.

So, how do we clearly define behavior?

DO:

1. DO: Describe what the behavior looks like

Make sure that you are describing what you are actually seeing. Rather than aggression, say he hit another child with an open palm. Instead of saying he had a tantrum, he fell on the floor and screamed. When I observe either of those behaviors with the second definition, I would know what I was looking for.

2. DO: Be specific

Rather than head-banging, say he hit his head with his closed fist. That’s different than if he was hitting his head on a hard surface, a different type of behavior.

3. DO: Be comprehensive

Give a full description of the behavior. Many times behaviors occur in clusters rather than as isolated behaviors. For instance, a child who falls on the ground, throws items in his hand, begins screaming and then gets up and starts coming toward the teacher, hitting her with his fists while crying and screaming has a chain of behavior that can be useful to note. That whole sequence of behavior seems to fit together, which is why we might call it a meltdown or a come-apart, so I wouldn’t describe it as each individual incident when they all seem to stem from the same source and be part of the same event. However, when you tell me he had a come-apart I might think he cried and screamed, I might not think that he began to approach the teacher and hit her. In addition, knowing that it’s a common chain of behavior tells me that if we can intervene when he falls on the ground, we might be able to prevent the hitting of the teacher.

4. DO: Be objective

There is nothing worse than reading a behavioral report on a student and reading the bias of the observer into it. Wilbur is a teacher who is exhausted from trying to manage Jim’s behaviors all year. So when Jim hits another student nearby, Wilbur’s data say “he attacked another student.” A more objective description would be he reached out and slapped another student. To me attacked might mean that he hit him repeatedly and showed other aggressive types of behaviors. To Wilbur it means Jim hit another kid. The behavior we are seeing in the same, but the words used make a difference in how its perceived and whether it is perceived as objective. On the flip side, it might be an outside consultant who observes a classroom at the request of a parent, advocate or administrator. The outside consultant might see Jim’s hitting and write, “When given no other option to get the child to move out of his way, Jim slapped at the other student to get him to move.” Same behavior, but completely different perspective. The more objective you write about the behavior, the more effective the assessment will be and the more others will believe that the observations are accurate.

DON’T

1. DON’T Use emotion words to describe the behavior

Don’t say he was angry at you when you mean that he hit you. You can’t know what his emotions actually are because you can’t observe them. Most of us can’t even, when upset, accurately describe our emotions. Think about a friend that you have asked, “Are you mad at me?” only to have her tell you that she’s not mad at you and then find out that she actually was based one what she told someone else. Or imagine that you know you shouldn’t be upset with someone so when they ask, you say no. In addition, emotions manifest themselves behaviorally differently for every person. Some people get very quiet when they get angry; other people throw things. Different behaviors, same emotion word. If you keep emotion out of it, you have a more well-defined behavior.

2. DON’T Include your supposed function in the definition of the behavior

This is hard for those of us who have looked at behavior as having a function. It’s easy to assume the function of the behavior and have it become part of our description. For instance, May is teaching Jim and he hits her and laughs. When asked about the behavior, May says, “He had attention-seeking behavior.” This doesn’t tell me what he did and it assumes the function. First, if we already knew the function of the behavior, we wouldn’t need the FBA. Second, the function you think it serves may be wrong so the definition itself may be misleading. In Jim’s case, his behavior was actually functioning to escape from the work task May was presenting; it was reinforced because every time he hit her, she turned away and ignored him, and he escaped from the task a little longer. Remember, thinks are always what they seem and the function is not part of the form of the behavior.

3. DON’T Describe things you can’t observe

This goes hand and hand with number 1, but bears repeating and expansion. It’s easy to say that he was depressed so he was upset. That tells me nothing about what he actually did. I have no idea what you saw or what the problem was. Telling me that he said he was always sad and then began to cry is a more accurate description of what I am able to observe. Another one is saying that he hit Jim to get back at him. Unless he told you that (in which case, I would say he said that he hit him because he wanted to get back at him) you didn’t observe that…all you observed was the hitting. This is not to say that feelings and thoughts don’t exist or don’t matter. It’s just to say that you can’t observe them and you can’t rely on their accuracy.

So remember, when defining the target behavior it’s important that we stick with the old Dragnet motto (yes, I know I’m dating myself again, but at least the movie is a bit more current?)–“JUST THE FACTS, MA’AM.” Stick to the facts and everyone on the team will be able to measure the behavior accurately to see how often it is happening before and after intervention and to take ABC data. Defining the behavior clearly is important as well because different people have different reactions to behavior. Whining is not that big a deal to me and I can ignore it; some can’t and when it’s in a classroom it can be very disruptive. However, if you told me the student had challenging behavior and didn’t tell me it was whining, I wouldn’t know what to look for and my data would be inconclusive because I might not record the whining.

Our next step is taking the defined behavior and prioritizing it and that’s where I will pick up next time.

Until then,